Every Move You Make: Visualizing Near-Future Motion Under Delay for Telerobotics

Abstract

Delays in direct teleoperation decouple operator input from robot feedback. We frame this not as a unitary problem but as three facets of operator uncertainty: (1) communication, when commands take effect, (2) trajectory, how inputs map to motion, and (3) environmental, how external factors alter outcomes. We externalized each facet through predictive visualizations: Network, Path, and Envelope. In a controlled study with 24 participants (novices in telerobotics) navigating a simulated robot under a fixed 2.56 s round-trip delay, we compared these visualizations against a delayed-video baseline. Path significantly shortened task time, lowered perceived cognitive load, and reduced reliance on reactive "move-and-wait" behavior. Envelope lowered cognitive load but did not significantly reduce reactive behavior or improve performance, while Network had no measurable effect. These results indicate that predictive support is effective only when trajectory uncertainty is externalized, enabling operators to move from reactive to more proactive control.

CCS Concepts

- Human-centered computing~Empirical studies in HCI

- Human-centered computing~Interaction techniques

- Computer systems organization~Robotics

- Computer systems organization~Robotic control

- Computer systems organization~External interfaces for robotics

1 Introduction

Telerobotics has long served as a way to extend human action into environments that are dangerous or inaccessible, ranging from handling radioactive material to military usage and exploring planetary surfaces [1, 2, 3, 4]. Rather than replacing people, robots augment human capability [5, 6, 7]: they provide mobility, precision and endurance, while humans contribute perception, judgment, and adaptation. This complementary relationship keeps human intelligence at the center of critical tasks and has made remote operation indispensable in high-stakes domains such as disaster response and planetary exploration.

The value of this partnership relies on prompt feedback between operator and robot. With increasing distances, communication delay becomes a defining constraint for interaction: round-trip communication delays from hundreds of milliseconds to many seconds decouple command and feedback. This leaves operators uncertain about when inputs take effect and whether their inputs lead to the expected outcomes.

Increasing levels of autonomy can mitigate the impact of delay, particularly in structured tasks where actions and outcomes are predictable [8, 9]. However, even advanced systems require oversight [10], and humans remain more flexible in unpredictable environments [11]. In these settings, delay forces operators to act under temporal uncertainty, where the timing and consequences of their actions are no longer immediately observable. Even modest delays of around 300 ms can degrade performance by misaligning operator expectations with actual system behavior [12, 13, 14]. Interfaces must therefore support humans in maintaining effective control under delay rather than removing them from the loop.

To understand why delays are so disruptive, it is useful to consider how operators normally learn to control a robot under delay-free conditions. In these settings, they gradually build a mental model of how input commands translate into robot behavior. For instance, pressing a forward key moves the robot a specific distance, or a turn input results in a predictable rotation. This control-to-motion mapping depends not only on kinematics but also on environmental factors such as terrain roughness or wheel slippage. Over time, operators refine their internal model through observation and adaptation, even accounting for visual cues such as soft soil or obstacles that signal potential changes in system response.

Delay fundamentally disrupts this calibration process. It obscures the immediate consequences of each action, weakens the temporal link between input and feedback, and slows operators’ ability to adjust their inputs. This makes it harder to refine a mental model of the system, especially in dynamic or uncertain environments. As a result, effective control under delay becomes not only a technical challenge, but a cognitive one [15, 16, 17].

One well-established mitigation strategy is "move-and-wait" behavior [18], where operators issue a command and then pause until delayed feedback confirms the result. While stabilizing, this behavior increases task time and cognitive load. From a cognitive perspective, temporal uncertainty forces operators to wait before feedback resolves, disrupting perception, comprehension, and projection of system state [16] and widening Norman’s gulfs of execution and evaluation [19], making it harder to know whether an action was effective or to anticipate the next state.

Technical countermeasures, such as network compensation, can reduce network variability, yet operators remain responsible for control under delay. Framing delay as temporal uncertainty rather than a communication defect shifts design focus from elimination to adaptation, motivating interface techniques that externalize the timing, consequences, and reliability of control actions [20, 21].

One long-standing interface approach to temporal uncertainty is the predictive display. These systems compute and visualize the robot’s near-future state [22, 23, 24]. By projecting likely behavior, predictive displays clarify the link between action and feedback and help operators anticipate outcomes [25, 26]. Predictive displays embody feedforward [27], providing perceptual cues that support projection in Endsley’s model of situational awareness [16] and narrowing Norman’s gulfs of execution and evaluation [19]. At design time, tools such as Choreobot [28] help identify where feedforward should be placed along task timelines to improve intelligibility in human-robot interaction.

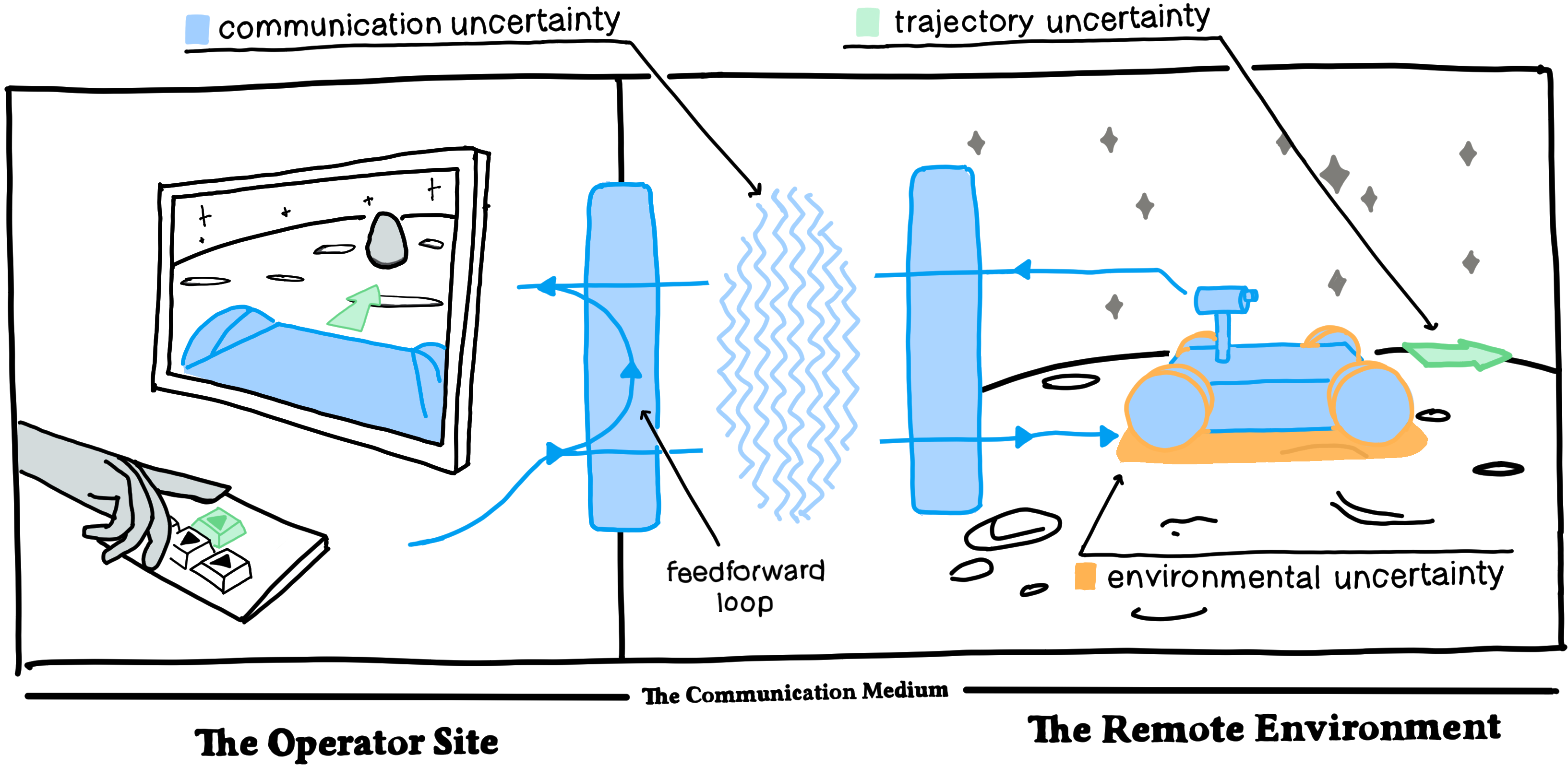

While predictive displays have demonstrated clear benefits in helping operators anticipate delayed responses, most have treated delay as a single, monolithic challenge [10]. However, delayed teleoperation exposes operators to multiple, interacting forms of uncertainty: when actions will take effect (communication delay), how issued commands will unfold over time (trajectory uncertainty), and how the environment will alter or disrupt expected outcomes (environmental uncertainty). Treating delay as a unitary phenomenon obscures how these sources interact and how interface support should be tailored to each.

Studying how interfaces can address these distinct uncertainties requires operating at a delay that is both cognitively challenging and still feasible for human-in-the-loop control. Delays in the two-to-ten-second range are known to mark a transition zone in which direct control becomes fragile and operators must increasingly rely on predictive or supervisory strategies [29]. We position our study at the lower bound of this intermediate range, using a 2.56 s round-trip delay, equal to the theoretical minimum for Earth–Moon communication [30]. This allows us to probe how uncertainty-aware support performs under demanding but still interactive conditions, which establishes a controlled, reproducible baseline: if addressing uncertainty meaningfully assists operators here, it provides a principled starting point for identifying when such support might begin to break down, creating clear opportunities for future work on longer and more variable delays.

To investigate how uncertainty can be externalized in practice, we introduce three visualization strategies that each target one of the identified uncertainty sources. The Network visualization reveals the timing of command execution, clarifying when inputs will take effect. The Path visualization projects the robot’s expected motion based on queued operator inputs. The Envelope visualization communicates how environmental variability may cause deviations from that projection. Together, these designs allow us to examine how different uncertainty representations support operators’ ability to plan, predict, and act under delayed feedback.

Therefore in this paper, we contribute:

- A decomposition of delay as operator uncertainty, distinguishing three key facets that affect control in delayed teleoperation: communication, trajectory, and environmental uncertainty. This extends prior work on predictive displays, which has often treated temporal delay as a single, unified problem.

- Three visualization techniques that explicitly externalize these uncertainty facets: a Network visualization to expose command timing, a Path visualization to project predicted motion, and an Envelope visualization to visualize potential deviations caused by environmental variability.

- A controlled study with 24 participants navigating a mobile robot under a fixed round-trip delay (2.56 s). We compared the three visualizations to a delayed-video baseline in terms of task performance, reactive behavior, and perceived cognitive load.

- Empirical evidence that trajectory-based feedforward (Path) significantly improved control performance by reducing task time, supporting more proactive input, and lowering cognitive load. The Envelope visualization reduced perceived cognitive load but did not yield stable performance benefits, while the Network visualization showed no measurable improvement over the baseline.

3 UNITE: A Teleoperation Simulation and Control Environment

To study teleoperation under delay, we developed UNITE, a Unity-based simulation environment. It provides reproducible conditions while allowing configurable manipulation of uncertainty factors such as noise, delay, and terrain. This ensures that visualization effects can be evaluated independently of uncontrolled variability.

3.1 Robot Dynamics

In UNITE, robot dynamics are implemented as modular components. This means that the motion equations and physical limits of the robot are encapsulated in interchangeable models. For our study we used the Turtlebot3 Waffle Pi, a differential-drive robot, with kinematics based on its wheelbase and motor specifications. To support more precise control in our environment, we reduced the maximum rotational speed from 1.82 radianpers to 0.30 radianpers. Because dynamics are modular, different robots can be loaded without altering the interface details.

3.2 Noise Model

To approximate imperfections in real robot motion, we implemented a deterministic noise model aligned with the kinematics of a differential drive robot. This model introduces variation in the robot’s motion by adjusting the commanded left and right wheel velocities according to six uncertainty sources, applied before each update of the robot state:

- Wheel slip: traction is reduced on rough terrain or at higher speeds, lowering effective velocity.

- Motor variation: small, time-varying differences between the left and right motors introduce drift.

- Terrain vibration: uneven ground causes oscillations that momentarily disrupt wheel-ground contact.

- Encoder noise: measured wheel velocities include small inaccuracies, simulating sensor error.

- Slope bias: when traversing inclines, load shifts unevenly across wheels, producing asymmetric motion.

- Wheel performance dynamics: time-varying factors including thermal effects, material deformation, and debris accumulation create oscillating differences in effective wheel performance.

Effects (3–4) are generated using Perlin noise, a smooth noise function that produces gradual rather than abrupt changes [58]. Unlike random noise, which jumps unpredictably, Perlin noise creates continuous patterns over space and time, which better matches how disturbances such as terrain roughness or motor noise occur. Effects (1–2, 4, 6) are based on velocity data, whereas effects (3, 5) are based on positional data.

The noise model is seeded deterministically so identical inputs produce identical deviations across conditions. Its parameters were iteratively calibrated to produce clear, realistic trajectory variations representative of normal rough-terrain motion. The role of this approximation is to introduce enough variability for environmental uncertainty to matter, while keeping that variability constrained so the visualization conditions (see Section 4) can be compared reliably.

3.3 Fixed-delay model and implementation.

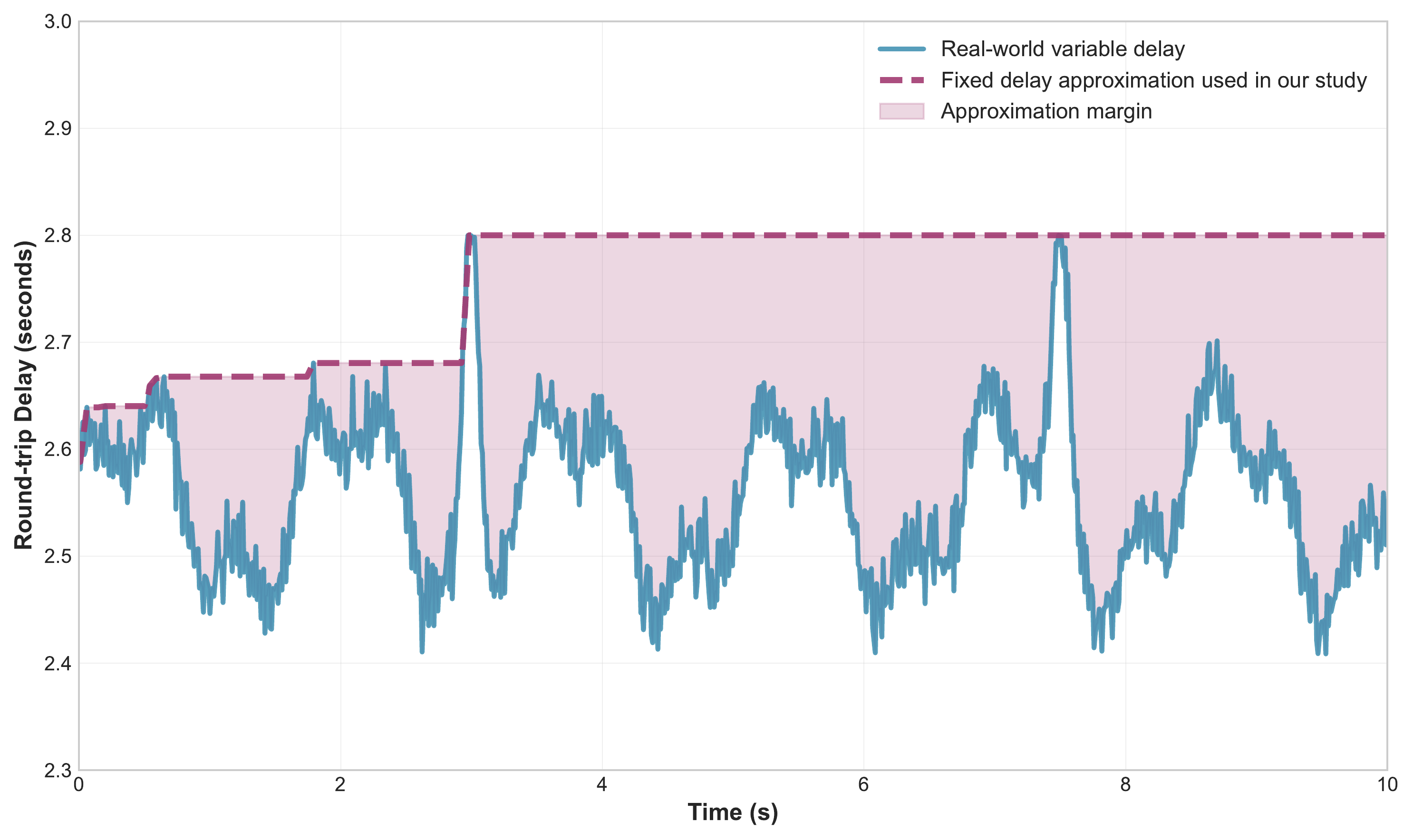

To isolate the effect of delayed feedback, UNITE applies a constant 2.56 s round-trip delay. Real networks often have variable delay, which can cause jitter, buffering, and dropped frames. This makes it harder to tell whether performance differences stem from the delay itself or from its fluctuations [12, 37]. A fixed delay removes this ambiguity. With a stable communication delay, we can compare how each visualization supports operator control [21, 20].

A fixed delay also reflects a practical abstraction. When delay varies within a known and bounded range, the system can treat the largest observed value as its effective delay (see Figure 1). This creates a consistent reference value for applying delay in the control loop. In UNITE, the fixed value is 2.56 s, which corresponds to the theoretical lower bound round-trip time for Earth to Moon communication [30], providing a concrete reference point for the scale of temporal separation implemented in the system. By enforcing a fixed delay, all interface conditions operate under the same temporal separation between action and feedback.

Technically, the delay is realized through a time-stamped command queue: inputs are stored with their execution times and applied only after 2.56 s. During this waiting period, queued commands are also used to generate the lookahead trajectories (Section 4), ensuring consistent delayed dynamics across all visualization conditions.

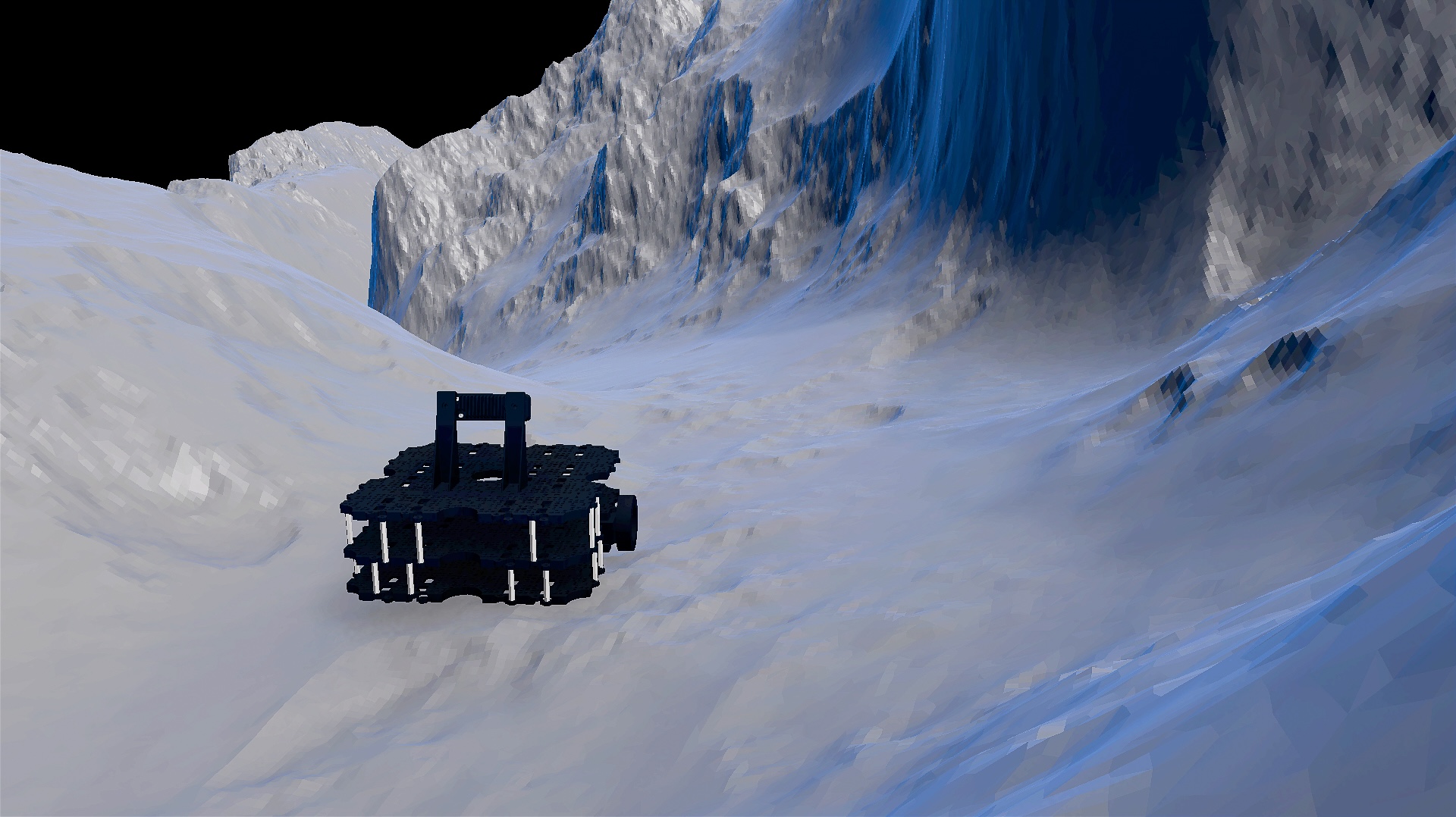

3.4 Environment Generation

Two terrains were generated in advance from publicly available displacement maps (Moonscapes). One terrain is used for training, and the other serves as the navigation environment. Both terrains remain fixed within the simulation, ensuring that rendering, physics integration and terrain-aware noise operate over consistent surface geometry.

The terrain supports two roles in the system. First, it provides the visual surface onto which trajectory predictions are projected so that visualizations follow local ground topology (see Section 4). Second, it acts as the collision and support surface for robot motion. The robot’s vertical position is updated via raycasting, while slope and roughness are estimated in real time using a three-point triangulation method. These terrain-derived values drive the position-based components of the noise model (effects 3 and 5), ensuring that disturbances originate from structured features of the surface rather than arbitrary perturbations.

To approximate lunar and space conditions, UNITE uses a single directional light (sun analog), no atmospheric scattering, and a dark sky. Figure 2 shows the simulated robot traversing one of the generated terrains. For clarity in this paper, lighting in Figure 2 was adjusted to make details of the robot and terrain more visible.

4 Externalizing Uncertainty in Teleoperation Interfaces

Effective teleoperation requires operators to form a reliable mental model of how their inputs affect robot behavior. Under delay, this becomes increasingly difficult: the temporal gap between input and feedback obscures the consequences of each action, weakening the ability to predict outcomes or adapt to changing conditions. These difficulties, however, originate from multiple sources, including ambiguity about when commands are enacted (communication uncertainty), how inputs translate into motion given the robot’s dynamics (trajectory uncertainty), and how environmental conditions such as terrain or slippage may alter the robot’s response (environmental uncertainty).

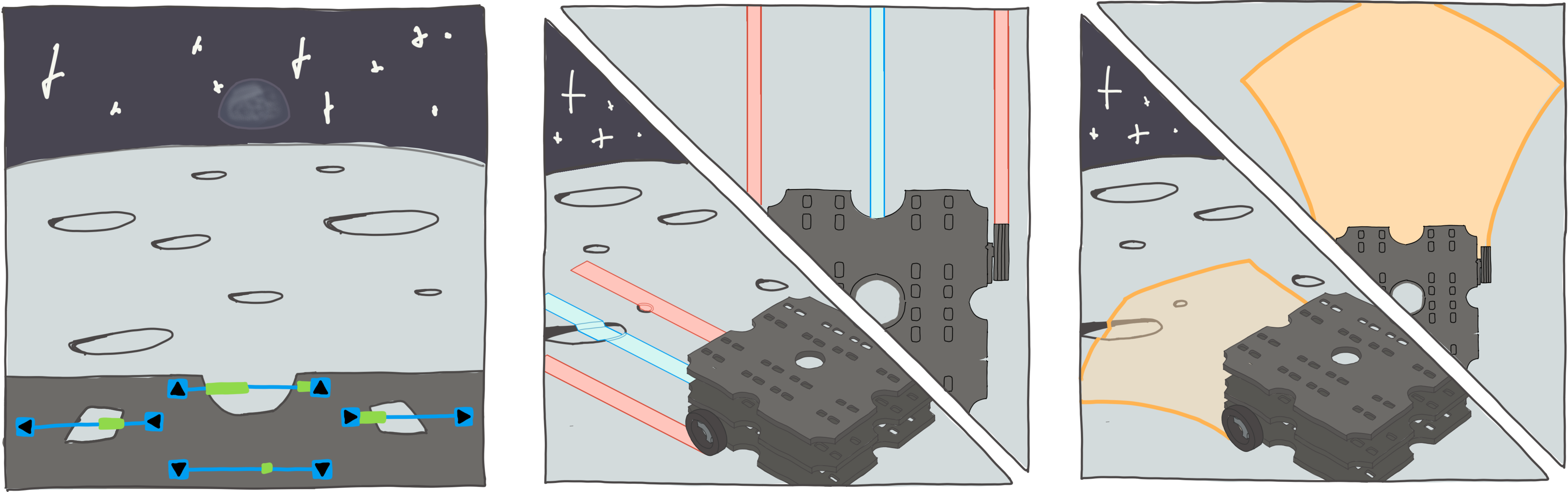

To support operator reasoning under delay, we designed three visualizations that each target one of these uncertainty sources (see Figure 3). The Network visualization makes the timing of command execution visible, externalizing communication delay. The Path visualization projects the robot’s expected trajectory based on current input, clarifying the mapping between control and motion through feedforward prediction. The Envelope visualization builds on the same predictive model but augments it with a visual representation of potential deviations caused by environmental variability. By externalizing distinct facets of uncertainty, these visualizations aim to support reduced reliance on reactive "move-and-wait" behavior, reduce cognitive load, and help operators maintain an accurate and adaptable mental model, even when immediate feedback is unavailable.

4.1 Network Visualization

The Network visualization targets communication uncertainty: the ambiguity about whether a command has been sent, and when its effects will become visible in the delayed camera feed (Figure 4). Under delay, this uncertainty forces operators to rely on memory or guesswork to keep track of input timing, which weakens their ability to coordinate actions effectively. For example, when approaching a turn, the operator must anticipate the delay and issue the turn command early enough for the robot to respond in time. To reduce this ambiguity, the Network visualization applies established HCI principles of system transparency and status visibility [19, 59]. It externalizes the command pipeline by visualizing the delay between input and execution, making command timing explicit and allowing operators to anticipate when their actions will take effect.

The Network visualization presents four parallel timelines, one for each arrow key, aligned spatially to match the layout of the physical keyboard. This spatial arrangement follows Norman’s principle of natural mapping [19], reinforcing intuitive associations between the user actions and the visualizations on the timelines. Each timeline functions as a communication channel, with the left side representing the operator’s input, and the right side representing the robot’s execution point. When a control signal is sent (arrow is pressed), a green block appears at the left end of the corresponding timeline. The block’s length encodes the duration of the keypress, and it animates rightward across the timeline, simulating the time it takes for the command to reach the robot, and the video feedback to propagate back—corresponding to the fixed communication delay (2.56 s). Once the block reaches the far end, the command is assumed to have taken effect and is observable in the delayed video feed. These timelines make the otherwise invisible delay visible and predictable. The steady animation speed provides a rhythmic, perceptible timeline that allows operators to offload timing calculations and anticipate when a command will take effect. Overlapping commands are displayed sequentially on their respective key channels.

Data Requirements. The visualization requires only input timestamps, keypress durations, control mappings, and the known fixed round-trip delay. It does not require access to robot pose, motion data, or kinematic models. As such, it offers a lightweight way to surface temporal uncertainty without introducing spatial prediction.

4.2 Path Visualization

The Path visualization addresses trajectory uncertainty: the difficulty of inferring how input commands will translate into robot motion under delay. Path visualization (Figure 5) does this by rendering a prediction in real-time of how input could translate into movements of the robot. Without explicit support, operators must mentally simulate the robot’s motion dynamics, which becomes increasingly error-prone as the delay grows. Such "predictive overlays" are an established design practice in vehicle interfaces (e.g., reversing camera path projections), where they help users anticipate the spatial outcome of steering. In delayed teleoperation, such feedforward cues allow operators to predict the robot’s behavior without waiting for delayed video feedback, thereby reducing the cognitive effort needed to maintain situational awareness.

The visualization projects where the robot will move next by applying an idealized motion model. It assumes perfect conditions: no wheel slippage, no external disturbance, and no environmental variability. The result is a feedforward prediction, an estimate of the robot’s path if the current command were executed exactly as intended. As shown in Figure 5, the interface overlays three trajectory lines on the video feed: one for each wheel and a third through the instantaneous center of rotation. These overlays update continuously with input: forward keypresses extend the lines outward, backward keypresses extend them inward, and left/right inputs bend them accordingly. Each segment is drawn cumulatively, so prior forward extensions remain visible when subsequent backward inputs are added. The trajectory length scales with the duration of keypresses and is capped by the fixed round-trip delay of 2.56 s, which defines the maximum lookahead window.

Kinematic Model. Trajectory prediction is computed using standard differential-drive kinematics: linear velocity $v = (v_L + v_R)/2$ and angular velocity $\omega = (v_R - v_L)/d$, where $v_L$ and $v_R$ are the left and right wheel velocities and $d$ is the wheelbase. These values are integrated forward in time to generate a continuous pose trace that approximates the robot’s motion over the lookahead window.

Data Requirements. Path visualization requires only three inputs: the robot’s current position, the user’s control commands, and the wheelbase parameter. These values define a noise-free kinematic model that predicts the trajectory the robot would follow under ideal execution. In our implementation, the position anchors the prediction in space, the commands define wheel velocities over time, and the wheelbase determines curvature. In our simulation, the robot’s current position is obtained directly from the Unity environment, control commands are captured from the keyboard input system, and the wheelbase is defined by the TurtleBot3 model. In real deployment, pose can be estimated via SLAM or GPS, user inputs are available directly from the control interfaces, and robot parameters are typically known from manufacturer specifications. Importantly, the visualization shows intended motion, not actual execution, reinforcing its role as a feedforward aid that supports planning and prediction.

4.3 Envelope Visualization

The Envelope visualization addresses environmental uncertainty: the variability in robot motion caused by environmental factors, such as slippage, terrain conditions, motor noise, or other external factors. The visualization extends the Path visualization: instead of projecting a single trajectory, it visualizes a cone-shaped region that represents the maximum possible deviation from the ideal path, given a set of modeled disturbances including terrain slippage and system noise (Figure 6). This visualization helps operators not only anticipate the robot’s intended direction, but also reason about how actual motion might diverge under uncertain environmental conditions.

As shown in Figure 6, the envelope is rendered as a translucent, cone-shaped region aligned with the robot’s apex point. The center of the cone shows the ideal, noise-free trajectory (identical to the Path visualization), while the left and right bounds mark the maximum deviation under modeled disturbances. The envelope dynamically expands in both width and length as keypress duration increases, up to the limit imposed by the fixed round-trip delay of 2.56 s. The shaded region thus reflects the cumulative effect of uncertainty over time. Importantly, this is not a probabilistic estimate, it reflects a worst-case spread, guaranteeing that the actual trajectory remains within the envelope under the modeled assumptions.

Kinematic Model. The model uses the same kinematic equations as the Path visualization ($v = (v_L+v_R)/2$, $\omega = (v_R-v_L)/d$), but modifies the input velocities to account for environmental disturbances. As detailed in the noise model (Section 3), six disturbances are modeled: wheel slip, motor variation, terrain vibration, encoder noise, slope bias, and wheel dynamics. While the simulation applies these disturbances dynamically via seeded noise, the Envelope visualization instead uses deterministic upper bounds derived from the same model parameters. These bounds are then propagated through the kinematic equations to compute the largest possible divergence from the intended trajectory. The adjusted velocities ($v’_L$, $v’_R$) define the left and right envelope boundaries.

Data Requirements. In our simulation, the Envelope visualization uses the robot’s current position (from the Unity environment), the user’s control commands (from keyboard input), the wheelbase (from the TurtleBot3 model). Disturbance parameters are sourced from the simulation’s noise model (Section 3). In real-world settings, obtaining reliable disturbance bounds is more challenging. Some parameters—such as slope or surface roughness—can be inferred from onboard sensors (e.g., LiDAR or stereo vision), while others, like motor slippage or vibration, are harder to sense directly and often require offline testing or empirical calibration. As such, practical deployment of this visualization would require careful tuning of the uncertainty model.

5 User Study: Evaluating Visual Feedback for Telerobotic Navigation with Delays

This study examines how the three different visualizations can reduce operator uncertainty in the direct control of UGVs under communication delay. The experimental task required participants to navigate a bounded environment (see Section 3.4) as quickly as possible. Accuracy was not measured independently, because the environment was designed to constrain large deviations: cliffs and boundaries prevented off-path driving and thus enforced a baseline level of accuracy. This design allowed task completion time to serve as the primary performance metric, ensuring that differences across conditions reflected control efficiency under delay rather than individual variations in speed–accuracy tradeoffs.

5.1 Study Objectives

The central challenge in delayed teleoperation is operator uncertainty: delayed feedback obscures when commands take effect, how they map to motion, and how environmental factors may alter outcomes. Without support, operators fall back on reactive "move-and-wait" control, which increases task time and cognitive load.

Our objective is to test whether externalizing the distinct facets of uncertainty through feedforward visualizations can reduce reliance on reactive control and improve direct teleoperation. This motivates the following research question:

What are the effects of the three facets of uncertainty on operator performance and cognitive load under delayed mobile teleoperation?

To answer this question, we test two hypotheses:

H1: Feedforward visualizations reduce task completion time under communication delay compared to delayed-video feedback alone.

H2: Feedforward visualizations will reduce subjective cognitive load under communication delay compared to delayed-video feedback alone.

5.2 Participants

We recruited 24 participants (M = 26.1 years, SD = 6.5, range = 20–44; 14 men, 10 women). Non-binary/other and prefer-not-to-say options were offered, although none were selected. All participants were novices; experts in telerobotics were not included in the study.

Participants were recruited via the research lab’s mailing lists and the research team’s personal networks. While this reflects a convenience sample, we sought variation in gaming background, as pilot observations suggested this might influence operator behavior. Gaming background was self-reported on a five-point scale: never (n = 7), less than once a month (n = 4), 1–3 times a month (n = 3), weekly (n = 3), or several times per week (n = 7). For exploratory analyses, we grouped participants into two categories: those who reported gaming at least weekly (coded as high gaming experience, $n=10$) and those who reported less frequent or no gaming (coded as low/no gaming experience, $n=14$).

All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The study was approved by the university’s Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC). Participation was voluntary, with no compensation, and participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

5.3 Setup and Apparatus

Participants used UNITE (see Section 3) to control a simulated UGV in a lunar-terrain environment (see Section 3.4). UNITE ran on a remote virtual machine (4 CPU cores, 8 GB RAM, 200 GB SSD, 200 Mbit/s network). The simulation ran at 50 Hz physics update and rendered at 120 FPS, streamed in real time applying a communication delay. The interface was presented in a 2560 $\times$ 1360 px browser window on a 27 inch Dell UltraSharp U2717D monitor (native resolution 2560 $\times$ 1440 px). Participants used a Logitech MX Keys keyboard with numpad, which they were free to position according to their preference.

We used a dual-window setup: one browser window hosted the Qualtrics questionnaire, while the second window was used for UNITE. The questionnaire window communicated with the experiment server to trigger the loading of condition sequences and to synchronize trial progression. UNITE continuously queried the server for updates and transmitted trials back to the central database on completion. All trial data was stored under unique participant identifiers and linked to the questionnaire responses. Questionnaires were hosted externally in Qualtrics, rather than integrated into the Unity interface, to ensure consistency in survey delivery, robust data export, and reduced development overhead.

5.4 Experimental Design

We used a within-subjects design: all 24 participants experienced four conditions: a Baseline showing only the delayed video feed, and three visualization conditions (Network, Path, Envelope). Order was counterbalanced with a Williams Latin square [60], assigning each of the four base sequences to six participants. The independent variable was the visualization’s information level (see Section 4). Dependent variables were completion time, perceived cognitive load (adapted NASA-TLX), responses to the post-condition questionnaire, and reliance on reactive "move-and-wait" behavior.

Task performance was measured as (a) completion time, defined as elapsed time from task start (click into the simulation window) to reaching the target within 300 s, and (b) completion rate for unsuccessful trials. Completion rate was the proportion of a reference trajectory reached (Figure 7). This trajectory was derived from successful attempts and discretized into 101 evenly spaced waypoints. For each unsuccessful trial, the participant’s endpoint was matched to the closest waypoint (Euclidean distance), and completion rate was defined as its index divided by 100.

Reactive "move-and-wait" behavior was coded as pauses of at least 2.56 s between inputs, matching the round-trip delay and Ferrell’s definition [18]. Reduced reliance on reactive behavior was coded as shorter intervals, indicating proactive input during motion.

Perceived cognitive load was measured with an adapted NASA-TLX [61], all items scored 0–20. The frustration item was excluded but captured in the final questionnaire for cross-condition comparison. We used the Mental Demand item as a proxy for cognitive load, following prior ergonomics and HCI work [62]. Additional measures included Likert ratings of visualization effectiveness, self-assessments of performance, efficiency, and mental model clarity. The comparative questionnaire captured relative rankings and open-ended feedback.

5.5 Procedure

Participants were seated behind a monitor. After a short study introduction, they read an information sheet on data handling, ethics, and voluntary participation, and gave informed consent. They then completed a demographics questionnaire (age, gender, gaming experience) and received task instructions describing training and study tasks, time limits (90 s training, 300 s study), and keyboard controls.

Each condition began in Qualtrics, which triggered the assigned visualization. The experimenter switched to the simulation window, where task instructions appeared. Input was accepted only after participants clicked into the window, ensuring keyboard focus and explicit awareness of task start.

Each condition included a short training task, followed by the main task. Training familiarized participants with terrain and visualization and lasted up to 90 s, ending automatically or via spacebar if participants felt prepared.

The study task required navigating to a target area (green circle) as quickly as possible within 300 s. The target was inspired by Mars Perseverance goal-setting [63]. Participants were instructed to drive forward to reach the path, which always began ahead of the start position. The target was initially not visible; participants were reminded to approach hills cautiously. Because the study examined visualization under delay rather than path-finding, participants could confirm with the experimenter whether they remained on the correct route. This safeguard reduced variance from disorientation and was applied sparingly. Success was defined as reaching the target within 300 s; otherwise, performance was measured as proportion of a reference trajectory reached.

After each condition, participants completed an adapted NASA-TLX, Likert items on visualization effectiveness, and short ratings of performance, efficiency, and mental model clarity, plus two optional open-ended questions on difficulties and advantages.

At the end of the study, participants completed a comparative questionnaire ranking the visualizations on usefulness, interpretability, perceived control, and frustration, followed by an open-ended question about preferred visualization and general comments. Informal feedback was recorded separately.

5.6 Quantitative Analysis

We analyzed 96 trials from 24 participants across four visualization conditions. Eight trials reached the 300 s ceiling, and an additional trial in the Path condition was flagged as a high outlier (282 s) by the $1.5\times IQR$ rule. All were retained because they reflect real operator difficulties. Analyses used within-subject non-parametric tests (Friedman with Wilcoxon post-hoc, Holm correction) and report effect sizes ($r = Z / \sqrt{N}$). Robustness checks excluding timeouts and the outlier produced consistent results. For the NASA-TLX items, we report Mental Demand and Performance, as they reflect perceived cognitive load and task performance best.

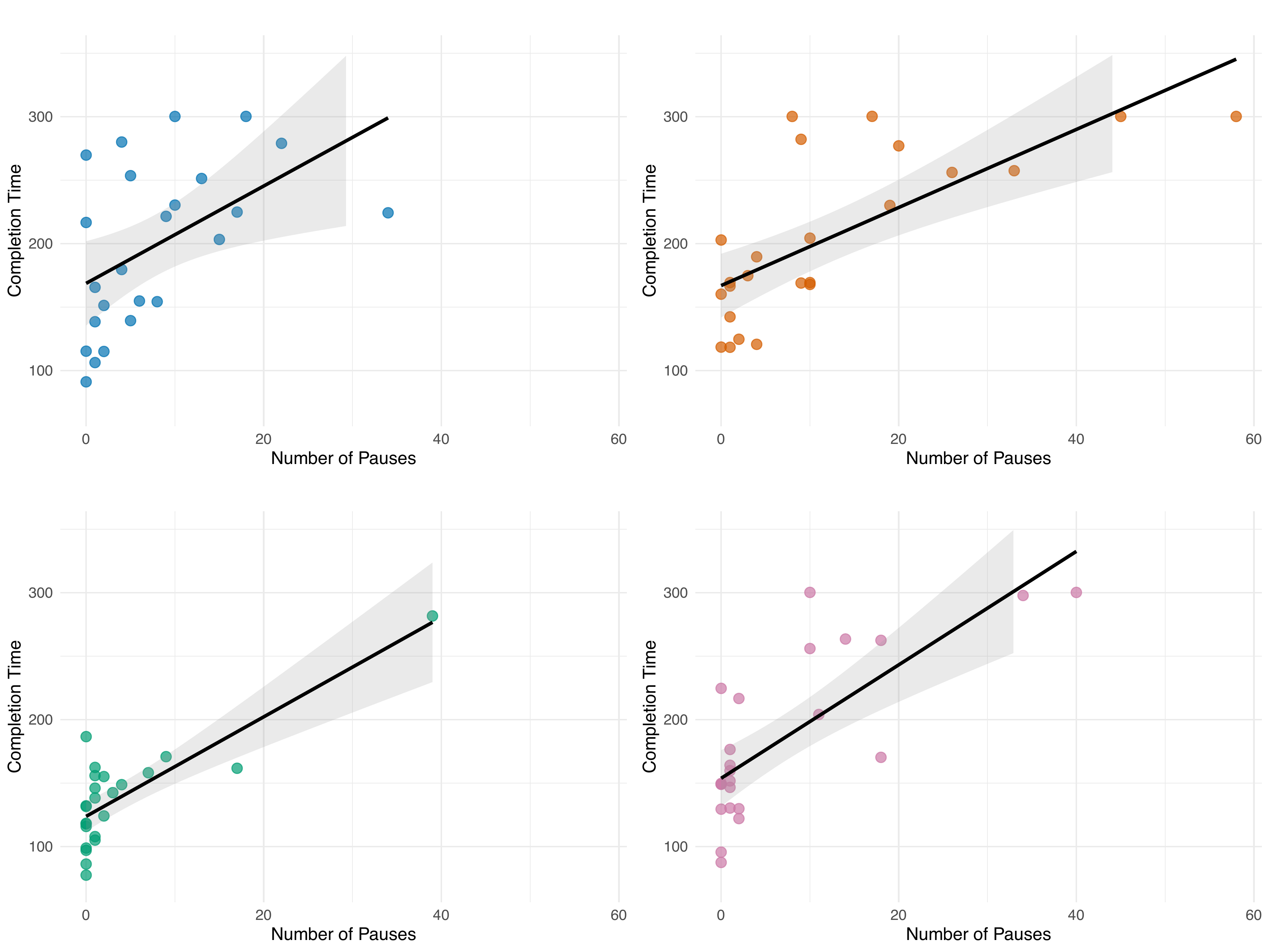

Task Completion Time. Completion times varied across conditions, with several trials reaching the 300 s ceiling, which were retained in the analysis (Figure 8(a)). Median times were shortest for Path (Mdn = 135.2 s) and longest for Baseline (Mdn = 209.9 s). A Friedman test showed significant differences ($\chi^2(3)=15.35, p=0.002, W=0.21$). Holm-corrected Wilcoxon tests found Path faster than Baseline ($p=0.008$, $r=0.65$), Network ($p=0.001$, $r=0.80$), and Envelope ($p=0.028$, $r=0.55$); Baseline, Network, and Envelope did not differ. Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 8(b)) confirmed this pattern: Path completed all trials, while the others showed slower progress and timeouts. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all dependent measures.

| Measure | Baseline | Network | Path | Envelope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M/SD) | (M/SD) | (M/SD) | (M/SD) | |

| Task Completion Time | 198.5 / 64.8 | 204.2 / 64.5 | 138.3 / 41.5 | 184.8 / 65.2 |

| Number of Pauses | 7.79 / 8.51 | 12.12 / 15.11 | 3.71 / 8.47 | 6.69 / 10.99 |

| Subjective Cognitive Load | 13.21 / 4.51 | 12.08 / 4.38 | 7.29 / 4.44 | 9.25 / 4.28 |

| Subjective Performance | 12.17 / 4.47 | 12.12 / 4.95 | 15.88 / 3.01 | 13.50 / 4.36 |

| Control | 1.46 / 0.59 | 2.21 / 0.83 | 4.25 / 0.90 | 3.17 / 0.96 |

| Ease of Interpretation | 2.67 / 1.43 | 2.88 / 1.26 | 4.33 / 1.01 | 3.62 / 1.21 |

| Understanding | 1.21 / 0.51 | 2.50 / 0.83 | 4.04 / 1.04 | 3.25 / 1.11 |

| Frustration | 3.58 / 1.06 | 3.04 / 1.33 | 1.46 / 0.72 | 2.46 / 1.06 |

These findings provide only partial support for H1: only the Path visualization improved completion time significantly. We performed independent-samples t-tests on the participant-averaged data, which showed that gaming experience did not affect completion time, High gaming experience ($n = 10$, $M = 171.9$, $SD = 35.9$), Low/No gaming experience ($n = 14$, $M = 188.3$, $SD = 49.2$), $t(22) = -0.95$, $p = .35$, $d = -0.37$.

Completion Rates. Completion rates, defined as the proportion of the reference path reached before timeout, were evaluated only for failed trials. Failures were rare: Baseline (2/24), Network (4/24), Path (0/24), and Envelope (2/24). When failures occurred, Baseline and Envelope trials typically ended close to the target (Mdn = 96% and Mdn = 90%), whereas Network failures stopped earlier and were more variable (Mdn = 73%, range 35–91%). Because the number of failures per condition was very small, these outcomes are reported descriptively only, as sample sizes were too small for reliable statistical testing.

Reactive "move-and-wait" Behavior. Reactive behavior, defined as pauses $\geq$ 2.56 s (matching the round-trip delay), occurred in 72 of 96 trials (75%). By condition: Baseline (20/24), Network (21/24), Path (14/24), Envelope (17/24). Pause counts differed significantly (Friedman $\chi^2(3)=17.59, p<.001, W=0.24$, see Figure 9). Medians were highest in Network (Mdn = 8.5, IQR [1.0–17.5]) and Baseline (Mdn = 5.0, IQR [1.0–10.8]), and lowest in Path (Mdn = 1.0, IQR [0.0–2.3]) and Envelope (Mdn = 1.0, IQR [0.0–10.3]). Post-hoc Wilcoxon tests with Holm correction showed significantly fewer pauses in Path than in Baseline ($p=0.012$, $r=0.22$) and in Path than in Network ($p=0.006$, $r=0.26$); other contrasts were non-significant. Thus, Path reduced reliance on "move-and-wait" compared to Baseline and Network, while Envelope showed similarly low medians but higher variability and no reliable differences. We performed independent-samples t-tests on the participant-averaged data, which indicated that gaming experience did not significantly affect reactive behavior, High gaming experience ($n = 10$, $M = 5.2$, $SD = 5.4$), Low/No gaming experience ($n = 14$, $M = 9.4$, $SD = 11.5$), $t(19.6) = -1.17$, $p = .26$, $d = -0.43$.

Pause durations were stable across conditions, with medians of Baseline (Mdn = 3.18 s, IQR [3.02–3.42]), Network (Mdn = 3.10 s, IQR [2.89–3.36]), Path (Mdn = 3.22 s, IQR [3.02–3.62]), and Envelope (Mdn = 3.14 s, IQR [2.93–3.38]). Although a Friedman test indicated overall differences ($\chi^2(3)=10.90, p=0.012, W=0.30$), Holm-corrected post-hoc tests found no reliable pairwise contrasts ($p_{\text{holm}} \geq 0.15$). This indicates that the frequency, rather than the length, of pauses varied systematically with condition.

Correlation Between Reactive Behavior and Completion Time. A mixed-effects model with random intercepts for participants showed that pause frequency (pauses $\geq$2.56 s) predicted completion time ($\beta=3.97$, 95% CI [3.09, 4.85], $p<.001$); each additional pause added about 4 s. For descriptive reference, a pooled Spearman correlation across all 96 trials was also large ($\rho=0.71$, $p<.001$). Condition-wise correlations with BCa bootstrap CIs (5{,}000 iterations) corroborated this pattern: Baseline ($\rho=0.57$, CI [0.15, 0.81]), Network ($\rho=0.72$, CI [0.47, 0.87]), Path ($\rho=0.66$, CI [0.21, 0.86]), and Envelope ($\rho=0.69$, CI [0.31, 0.87]); all remained significant after Holm correction. Together with stable pause durations across conditions, these results indicate that pause frequency, not length, drove completion time (see Figure 10).

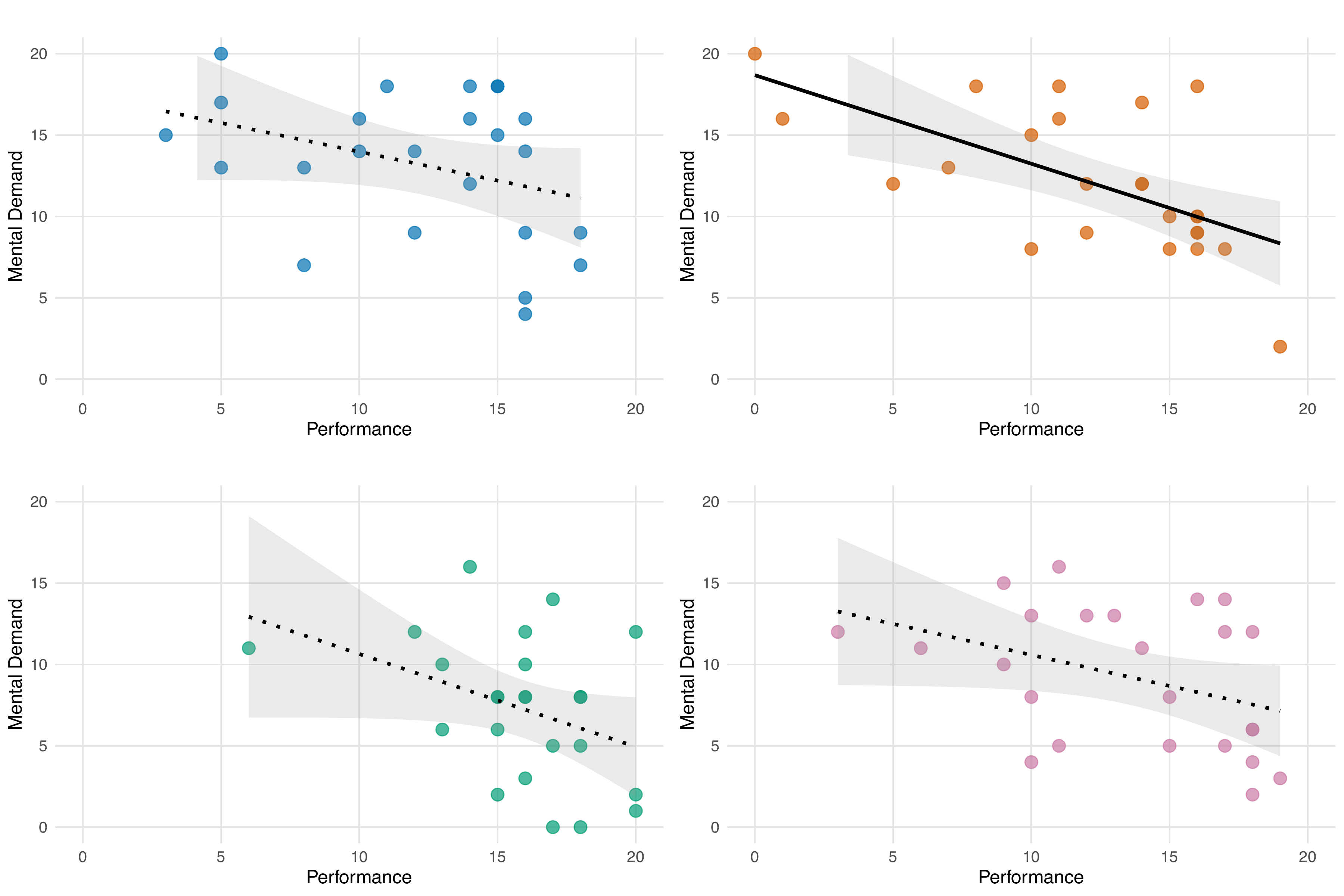

Subjective Cognitive Load. Subjective cognitive load, measured with the NASA-TLX Mental Demand item (0–20 scale), differed across conditions. Scores were highest in Baseline (M=13.21, SD=4.51) and Network (M=12.08, SD=4.38), lower in Envelope ($M=9.25, SD=4.28$), and lowest in Path (M=7.29, SD=4.44). A Friedman test indicated differences ($\chi^2(3)=33.20, p<.001, W=0.46$). Post-hoc Wilcoxon tests (Holm corrected) showed that Path reduced demand compared to all other conditions ($p<.03$), and Envelope reduced demand compared to Baseline and Network ($p=.005$); Baseline and Network did not differ ($p=.45$).

These results provide partial support for H2. Path reduced demand most; Envelope reduced demand relative to Baseline and Network; Network matched Baseline. Thus, not all uncertainty facets are equally effective: externalizing the reference path lowered demand, whereas visualizing network delay added cues without measurable benefit.

Subjective Performance. Perceived task performance, measured with the NASA–TLX (0–20 scale, reverse-coded so that higher values indicate better perceived performance), differed across conditions. Ratings were highest in Path (M = 15.88, SD = 3.01), followed by Envelope (M = 13.50, SD = 4.36), Baseline (M = 12.17, SD = 4.47), and Network (M = 12.12, SD = 4.95). A Friedman test indicated a significant effect ($\chi^2(3)=20.09, p<.001$, $W=.28$). Post-hoc Wilcoxon tests (Holm corrected) showed that Path was rated higher than Baseline ($p=.002$, $r=.79$), Network ($p<.001$, $r=.85$), and Envelope ($p=.037$, $r=.43$). No other contrasts were significant. Thus, only Path improved subjective performance relative to the alternatives.

Relations Among Performance, Cognitive Load, and Completion Time. To assess alignment between subjective ratings and objective outcomes, we examined correlations among perceived performance (NASA-TLX), perceived cognitive load, and completion time within each condition. We expected higher self-rated performance to align with shorter times and lower demand, and higher demand to align with longer times. Spearman correlations with BCa bootstrap confidence intervals (5{,}000 iterations) and Holm correction ($3 \times 4$ tests) showed that most associations were negative, as expected, but did not reach significance after correction. The only robust effect appeared in the Network condition, where higher perceived performance was strongly associated with lower perceived cognitive load ($\rho=-.62$, 95% CI $[-.85,-.18]$, $p_\text{Holm}=.016$). Other correlations, such as performance vs.\ time in Path and Envelope, were negative but did not survive correction (all $p_\text{Holm}>.08$). Overall, convergence between subjective and objective indicators was limited, with reliable alignment only under the Network visualization (Figure 11).

Comparative Questionnaire Responses. Comparative questionnaire responses (Likert ratings, rankings, and open-ended preferences) converged on a clear preference for Path. Path received the highest Likert ratings for control ($M{=}4.25, SD{=}0.90$), understanding ($M{=}4.04, SD{=}1.04$), and ease of interpretation ($M{=}4.33, SD{=}1.01$), and the lowest for frustration ($M{=}1.46, SD{=}0.72$). It was most often ranked first for control (19/24, 79%), performance (15/24, 63%), and helpfulness (18/24, 75%).

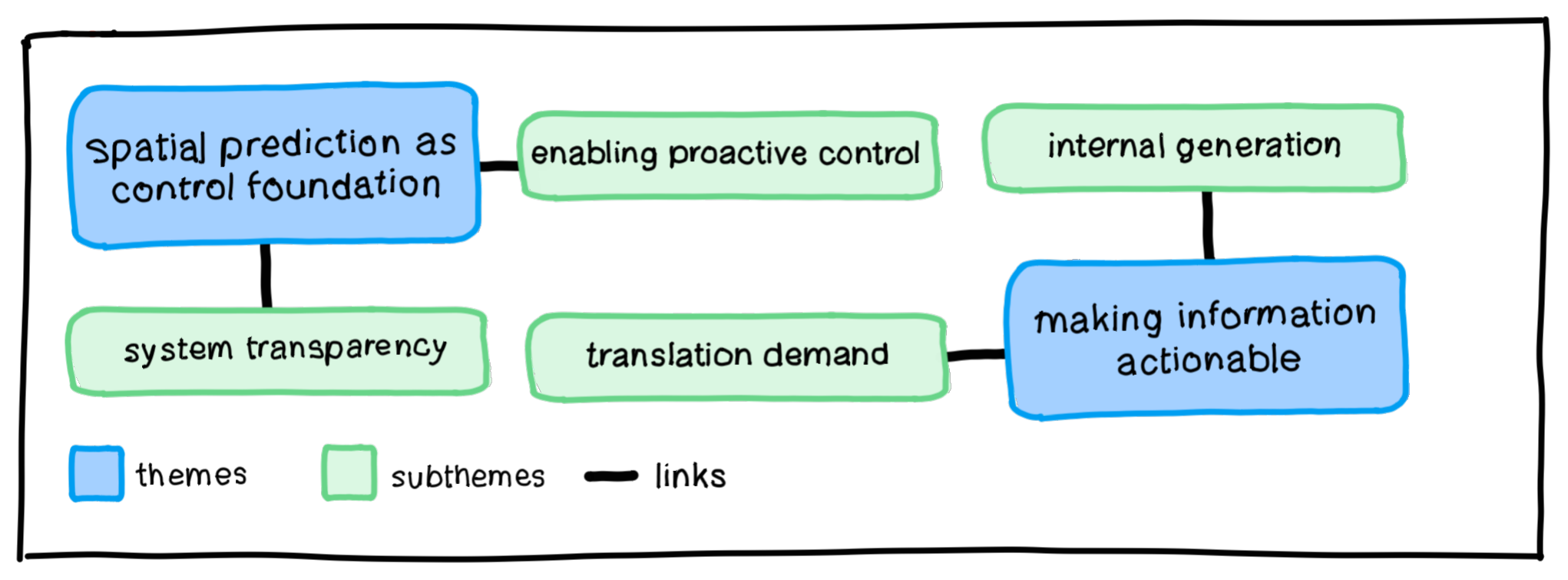

5.7 Qualitative Analysis

To examine participants’ subjective experiences of teleoperation under delay, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis [64]. Adopting an essentialist epistemology, we treated participant responses as direct reflections of their experience, prioritizing semantic content over latent interpretation. The analysis followed a systematic, data-driven process in which two authors first coded the dataset independently to establish an initial pool of descriptive codes, documented in a codebook with inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure consistent coding and minimize overlap between conceptually similar codes (Table 2). These codes were then reviewed collaboratively to develop a shared understanding of their meaning. During theme development, we treated codes as provisional and grouped together codes that described the same underlying idea. By collapsing these related codes into broader patterns, we moved from individual observations toward the themes presented below (see Figure 12).

Theme 1: spatial prediction as control foundation. Spatial prediction was the central concept that shaped how participants understood control under delay. Participants consistently treated control as the problem of acting without knowing where the robot would end up, rather than a problem of judging when their inputs would take effect. Participants described control as feeling deliberate, when a visualization showed a clear future position, and it became reactive when that position was uncertain. The theme captures this shared view, with subthemes showing how operators separated prediction that supported purposeful action from information that described system behavior but did not help them control it.

The subtheme enabling proactive control captures cases where a clear endpoint allowed operators to plan ahead rather than constantly fixing mistakes. Participants described the Path visualization as enabling deliberate anticipation: "the feedforward provided by the path visualizations helped me adapt my actions" (P11, Path). Other participants used the predicted path to regulate their timing, explaining that "the change in visualization showed me that I needed to halt my inputs, reassess, and consider my actions carefully" (P5, Path). Several noted that this shift toward planning reduced frustration, stating that "the task was much less frustrating" (P15, Path) when a stable future position was visible. We interpreted this pattern as showing that prediction improved control because participants could plan their movements instead of constantly correcting them.

The subtheme system transparency captures situations where visualizations clarified the robot’s behavior but still did not provide the clear future position needed for confident control. Participants valued cues about timing and possible drift but found them difficult to turn into reliable action. Some reported that rotation was easier to judge, noting that "during rotation it was clearer when the rotation would finish" (P12, Network). Others used the Envelope to assess risk, explaining that "you can see if the robot would hit a rock" (P24, Envelope). Despite this, participants stressed that these cues did not help them steer, stating that "it makes me understand what will happen but it’s not supportive of controlling the robot" (P2, Network). When the visualization felt too spread out to act on, some focused on a single point to keep it usable: "in the end I mainly looked at the middle corner of the yellow surface" (P12, Envelope). We understood this as transparency improving understanding, but without a clear future position to guide action, it could not support effective control.

Theme 2: making information actionable. This theme captures how participants experienced control as something they had to work out themselves when the system no longer showed a clear future position. Participants repeatedly described receiving information they could not act on until they transformed it into spatial expectations. This shift made control a mental task: instead of responding to a predicted outcome, operators had to create that outcome through their own judgment. We interpreted this as a pattern where prediction shifted to the operator, requiring them to build the robot’s future position from their own reasoning rather than from the video feed. The subthemes show how operators handled this shift either by converting non-spatial information about the robot’s state into a future position, or by creating that position themselves when the system offered no information at all.

The subtheme translation demand captures cases where participants converted non-spatial cues into spatial predictions. They described the mental load directly: "I had to multitask more in analyzing the arrows I pressed and should press in the future" (P21, Network); "this condition required more mental input as I was focused on timing my inputs" (P24, Network). Some improved with practice: "At the start it seemed very bad, but I learned throughout" (P16, Network). Others used calibration strategies: "I tested in the training phase what the distance or the angle is for a full bar" (P8, Network). But translation came with tradeoffs: "I felt like I could be more precise but anticipated uncertain terrain less, as this required me to be more focused" (P5, Network). For some, it produced distraction: "The visualization made it more confusing, it added a level of distraction" (P20, Network), or was only useful reactively: "I only really looked at this when I had already ended up in a problematic situation" (P12, Network). We interpret this as a case of resource competition: the mental effort required to translate these cues consumed the attention that operators otherwise needed to plan ahead.

The subtheme internal generation captures cases where participants constructed predictions entirely from internal resources when no external cue existed. Some formed workable strategies: "imagining a ‘ghost car’ it was easy to predict where the robot would turn" (P2, Baseline); "I would turn a certain amount of time and hence ‘pre-fire’ that input if I anticipated that I would need to turn" (P5, Baseline). Others adapted over time: "After some time I learned to think ahead for my robot" (P16, Baseline). But internal generation was fragile. Environmental uncertainty disrupted predictions: "I noticed that it was harder to overcome uncertain terrain when in this situation" (P5, Baseline); "I had trouble anticipating difficult terrain" (P5, Baseline). Some reported abrupt failures: "even when at some point I thought I ‘mastered’ the actions to compensate the delay, I just ‘got stuck’" (P11, Baseline). Others noted the full burden of unsupported control: "No visualization of the delay made it much more difficult to interpret" (P22, Baseline). Still, some described creative effort when support was absent: "I realized that the system would not provide me any help and that it was ‘all on me’ inciting me to be more creative" (P5, Baseline). We interpret this pattern as showing that internally generated predictions can support control, but they are fragile and quickly lose reliability when the environment becomes uncertain.

6 Discussion

Our findings show that predictive support improves delayed teleoperation only when the visual cues externalize uncertainty in a form that directly matches operators’ control demands. As Moniruzzaman et al. [10] note, most predictive displays provide deterministic future-state estimates and rarely incorporate uncertainty or differentiate its sources. We addressed this gap by decomposing delay into communication, trajectory, and environmental uncertainty and comparing visualizations that externalize each facet. Only Path improved task completion time and consistently reduced cognitive load, whereas Network and Envelope did not show comparable performance effects. These results indicate that predictive support becomes effective only when the visualization aligns with the operator’s control demands.

Effective control under delay relies on the operator’s ability to visualize the robot’s future position before committing to an input. This finding echoes Louca et al. [65], who identify predictable forward behavior as a prerequisite for maintaining operator trust. The fundamental challenge here is that operators must act before feedback arrives, meaning control is only viable when the future state is explicitly shown rather than inferred. As one participant noted, "the feedforward provided by the path visualizations helped me adapt my actions" (P11). This confirms feedforward theory, which suggests that making the outcome of an action visible narrows Norman’s gulf of execution [19, 27]. By explicitly projecting these spatial consequences, the Path visualization bridged this gap and enabled a shift from reactive to proactive control.

Comparisons across conditions reveal that predictive cues are effective only when they minimize the cognitive effort of converting information into spatial control. While the Network visualization clarified timing, it forced operators to convert temporal cues into spatial expectations, resulting in continued reliance on reactive strategies. Similarly, the Envelope provided spatial bounds that were useful for monitoring risk, but often too broad or physically unrealistic to guide steering. Because it supported error detection without offering a committed trajectory, the Envelope visualization reduced subjective workload but failed to improve control performance. This pattern supports findings that mismatches between prediction and outcome can undermine trust [55]: in this case, the Envelope visualization made uncertainty visible but not actionable, creating a critical gap between what participants understood and what they could actually control.

Analysis of reactive behavior reveals that operators pause not because of general uncertainty, but specifically to compensate for missing spatial prediction. While pause durations remained stable across all conditions, the frequency of pauses spiked whenever the interface failed to show a committed trajectory. Lacking external support, participants were forced to rely on fragile internal strategies, such as mentally simulating a "ghost car" to anticipate the robot’s path. However, these internal models often failed when terrain unpredictability introduced deviations the operators could not foresee. This suggests that the Path visualization succeeds because it functions as a robust, externalized version of the mental model operators struggle to build during training. By directly displaying this action-outcome mapping, the system removes the cognitive burden of internal simulation, ensuring control remains stable even when environmental conditions shift.

These results converge on an actionability gap: predictive cues improve control only when they directly specify the future state operators must act upon. While the Network and Envelope visualizations provided accurate data, they forced operators to perform demanding mental calculations to extract a driveable path. The Path visualization eliminated this cognitive tax by aligning the display with the spatial decisions required for navigation. This advantage becomes crucial as delays extend into the two-to-ten-second range where direct control remains feasible [29]. As delay increases, the lookahead window grows and internal prediction becomes less reliable. Consequently, effective teleoperation under significant delay requires shifting focus from visualizing the mechanics of uncertainty to projecting the clear, committed trajectory that enables operators to act.

Our findings reinforce a broader implication for delayed teleoperation interfaces: predictive cues should stay tightly coupled to the spatial decisions operators must make, which in practice means keeping an intended Path projection as the primary feedforward and navigation reference. However, in real deployments, especially over missions with longer delays, the reliability of this preview will drift as terrain, traction, and robot dynamics change. Rather than treating the projected Path as a fixed "best guess," systems can keep it adaptive by continuously re-validating the predicted motion against incoming state estimates and terrain cues available to the robot, such as slope, roughness, or likely slip. Reduced confidence can then be reflected directly in the same Path projection by shortening the preview horizon or deemphasizing less reliable segments, so that what remains visible stays driveable and aligned with what the operator is trying to achieve next. This supports a simple planning-update model in which the interface repeatedly recomputes the predicted Path, estimates near-future risk, and adjusts how far ahead it provides a committed reference over time. Such continuous feasibility checking is already common in field robotics, for example in planetary navigation [66], and provides a concrete route toward maintaining effective operator planning under prolonged and potentially increasing environmental instability.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that simply visualizing uncertainty is insufficient for effective control under delay. Predictive cues must match the representational form of operator decisions. While foundational work on predictive displays [23, 51] validated the utility of trajectory visualization, it largely treated delay as a unitary problem. Our decomposition clarifies the mechanism behind those early successes: trajectory prediction works not because it provides more information, but because it ensures representational compatibility between the interface and the task. Although timing and environmental information offered valid data, they forced operators to perform the cognitive labor of interpreting what this information meant for the robot’s future position. This extra effort prevented valid information from supporting a shift to proactive control. In this sense, our findings extend existing feedforward taxonomies [56] by establishing a boundary condition: in spatial control tasks, effective predictive displays must externalize the specific future state that operators can directly act upon, rather than merely exposing the underlying mechanics of uncertainty.

7 Limitations and Future Work

This study employed a fixed 2.56 s round-trip delay to create a stable experimental baseline, isolating operator performance from the variability introduced by jitter, buffering, and other forms of fluctuating delay. While real-world communication links often exhibit such variability, understanding how operators manage a consistent delay is a prerequisite for understanding how they respond when that delay begins to fluctuate. Our results therefore separate the cognitive effects of delayed feedback from the effects of its variability, providing a controlled foundation for future evaluations in which delay changes over time. Demonstrating that spatial feedforward resolves the cognitive challenges of a fixed delay establishes the basis for examining how predictive support performs when the communication delay becomes variable.

Our simulation used static terrain to maintain reproducibility while evaluating the three facets of uncertainty. Real deployments, however, often involve changing terrain conditions, and other actors or systems may continue to move during the communication gap. Under such circumstances, reactive "move-and-wait" behavior fails more fundamentally: by the time delayed feedback arrives, the environment or the positions of other agents may have shifted, making the delayed camera view an unreliable basis for action. The static environment allowed us to verify how the visualizations function, but increased environmental variability and independent movement will widen the gap between reactive and proactive control. As these factors grow, timely action becomes essential for maintaining stable operation under delayed feedback.

Our participant pool consisted of novices, which differs from operational contexts where experienced teleoperators develop internal models tuned to familiar delay conditions. Prior work shows that these internal models remain vulnerable when delays deviate from what operators have learned: Louca et al. [65] report that even experienced operators required additional operating time to adapt when an unexpected delay fault was introduced. This indicates that robustness to delay is conditional rather than absolute. Externalized trajectory prediction therefore provides a stabilizing reference for both novices and experts when the communication delay or environmental conditions fall outside their learned range.

Finally, while we measured task completion time and perceived workload to evaluate immediate control performance, we did not assess longer-term constructs such as situational awareness, trust, or attention allocation. Our findings with the Envelope visualization show that visualizing environmental uncertainty does not necessarily translate into improved operator confidence or control. Future work should therefore examine how committed trajectory predictions, such as those in the Path visualization, influence trust calibration and mitigate the uncertainty loops that arise during extended remote operation.

8 Conclusion

Communication delay separates operator input from robot feedback and forces operators to rely on prediction rather than perception. We examined this problem by distinguishing three facets of uncertainty created by delay: communication, trajectory, and environmental. We then evaluated visualizations that externalize each facet. In a controlled study with a fixed 2.56 s round-trip delay, only the Path visualization, which displayed near-future motion as a committed trajectory, reduced task completion time, lowered perceived cognitive load, and decreased reliance on reactive "move-and-wait" behavior. The Envelope visualization reduced perceived cognitive load but did not produce comparable performance gains, and the Network visualization showed no measurable improvement beyond delayed-video feedback alone. These findings show that simply visualizing uncertainty is not enough. Predictive cues must align with the spatial decisions operators need to make. For direct teleoperation under delay, showing the trajectory the robot will follow makes it clear where the robot would end up, which emerges as the most effective feedforward strategy for restoring proactive control.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Flemish Government under the "Onderzoeksprogramma Artificiële Intelligentie (AI) Vlaanderen" program, R-13509, and by the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Hasselt University, BOF23OWB29. The infrastructure for this work is funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU project MAXVR-INFRA and the Flemish government.

9 Thematic Analysis Codebook

| Code | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| current state info |

Referring to information provided by the visualization about the robot’s current condition or situation. | "It was useful to know that the robot would stay in between the yellow parts." | |

| future outcome info |

Referring to information provided by the visualization about what the robot will do next, how its movement will end, or where the robot will end up after an input. | Exclude cases describing the participant’s own prediction of the robot’s behavior rather than information presented by the visualization. | "The visualization increasing in size made it clear how far the robot would be after the delay, which worked very well." |

| anticipate behavior |

Predicting, foreseeing, or mentally projecting the robot’s future movement. | "Seeing the different inputs being sent, I could plan ahead to combine inputs." | |

| visualization reduction |

Explicitly describing using only part of the available visualization, including focusing attention on a specific visual element rather than the full display. | "I mainly looked at the middle corner of the yellow surface." | |

| control difficulty | Explicitly stating difficulty operating, directing, or executing intended robot movement. | Exclude statements describing difficulty specifically related to turning behavior. | "It was harder to control the robot, even when at some point I thought I ‘mastered’ the actions." |

| turning difficulty | Explicitly stating difficulty turning the robot. | "I struggled even more with rotation in this version." | |

| error correction info |

Explicitly stating that the visualization helped detect, understand, or correct mistakes that occurred during navigation or control. | "It clearly indicated when I had to go back because I wouldn’t make the turn." | |

| task difficulty | Explicitly stating that the task became easier or harder due to something in the visualization or the interaction. | "The lack of any feedforward made the task harder." | |

| temporal effect | Explicitly describing how delay, or temporal mismatch affected control, decisions, or performance. | "The delay really affects the decisions made during the robot maneuvers." | |

| terrain effect | Explicitly describing how terrain or surface features affected navigation or performance. | "I crashed into some hills that I did not expect the robot to struggle with." | |

| learning effect | Explicitly stating that skill, familiarity, or confidence improved due to prior exposure to the task, robot, or interface. | "I knew what task I needed to perform because of the previous condition." | |

| emotion | Explicitly describing an emotional reaction in response to the visualization, the task, or the robot’s behavior. | Exclude emotional reactions that are clearly attributable to performance issues, control difficulties, timing effects, or terrain-related effects. | "I made it to the end, but the way there was terribly frustrating." |

References

- Raymond C Goertz and Individual. 1949. US2632574A - Remote-control manipulator - Google Patents. https://patents.google.com/patent/US2632574#patentCitations

- Carlos Marques, João Cristóvão, Paulo Alvito, Pedro Lima, João Frazão, Isabel Ribeiro, and Rodrigo Ventura. 2007. A search and rescue robot with tele‐operated tether docking system. Industrial Robot: An International Journal 34, 4 (2007), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/01439910710749663

- R.R. Murphy. 2004. Activities of the rescue robots at the World Trade Center from 11-21 september 2001. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 11, 3 (2004), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2004.1337826

- D. W. Hainsworth. 2001. Teleoperation User Interfaces for Mining Robotics. Autonomous Robots 11, 1 (2001), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011299910904

- Thomas B Sheridan. 1992. Telerobotics, automation, and human supervisory control. MIT press, Cambridge, MA, United States.

- Terrence Fong, Charles Thorpe, and Charles Baur. 2003. Collaboration, Dialogue, Human-Robot Interaction. In Robotics Research. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 255–266.

- Michael A Goodrich, Alan C Schultz, and others. 2008. Human–robot interaction: a survey. Foundations and trends® in human–computer interaction 1, 3 (2008), 203–275.

- Chen Min, Shubin Si, Xu Wang, Hanzhang Xue, Weizhong Jiang, Yang Liu, Juan Wang, Qingtian Zhu, Qi Zhu, Lun Luo, Fanjie Kong, Jinyu Miao, Xudong Cai, Shuai An, Wei Li, Jilin Mei, Tong Sun, Heng Zhai, Qifeng Liu, Fangzhou Zhao, Liang Chen, Shuai Wang, Erke Shang, Linzhi Shang, Kunlong Zhao, Fuyang Li, Hao Fu, Lei Jin, Jian Zhao, Fangyuan Mao, Zhipeng Xiao, Chengyang Li, Bin Dai, Dawei Zhao, Liang Xiao, Yiming Nie, Yu Hu, and Xuelong Li. 2024. Autonomous Driving in Unstructured Environments: How Far Have We Come? https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.07701

- Ruihe Wang, Yukang Cao, Kai Han, and Kwan-Yee K Wong. 2024. A Survey on 3D Human Avatar Modeling–From Reconstruction to Generation. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04253

- MD Moniruzzaman, Alexander Rassau, Douglas Chai, and Syed Mohammed Shamsul Islam. 2022. Teleoperation methods and enhancement techniques for mobile robots: A comprehensive survey. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 150 (2022), 103973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2021.103973

- Ramviyas Parasuraman, Sergio Caccamo, Fredrik Båberg, Petter Ögren, and Mark Neerincx. 2017. A New UGV Teleoperation Interface for Improved Awareness of Network Connectivity and Physical Surroundings. arXiv:1710.06785. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.06785

- Stefan Neumeier, Philipp Wintersberger, Anna-Katharina Frison, Armin Becher, Christian Facchi, and Andreas Riener. 2019. Teleoperation: The Holy Grail to Solve Problems of Automated Driving? Sure, but Latency Matters. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1145/3342197.3344534

- Sidharth Bhanu Kamtam, Qian Lu, Faouzi Bouali, Olivier C. L. Haas, and Stewart Birrell. 2024. Network Latency in Teleoperation of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: A Review of Trends, Challenges, and Mitigation Strategies. Sensors 24, 3957 (2024), 3957. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24123957

- Zhaokun Chen, Wenshuo Wang, Wenzhuo Liu, Yichen Liu, and Junqiang Xi. 2025. The Effects of Communication Delay on Human Performance and Neurocognitive Responses in Mobile Robot Teleoperation. In 2025 17th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics (IHMSC). IEEE, Hangzhou, China, 63-67. https://doi.org/10.1109/IHMSC66529.2025.00020

- Peter Kazanzides, Balazs P Vagvolgyi, Will Pryor, Anton Deguet, Simon Leonard, and Louis L Whitcomb. 2021. Teleoperation and visualization interfaces for remote intervention in space. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 8 (2021), 747917.

- Mica R. Endsley. 1995. Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems. Human Factors 37, 1 (1995), 32-64. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872095779049543

- Felix Tener and Joel Lanir. 2022. Driving from a Distance: Challenges and Guidelines for Autonomous Vehicle Teleoperation Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3501827

- William R. Ferrell. 1965. Remote manipulation with transmission delay. IEEE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics HFE-6, 1 (1965), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1109/THFE.1965.6591253

- Don Norman. 2013. The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded edition. Basic books, New York, NY, USA.

- Nadia Boukhelifa and David John Duke. 2009. Uncertainty visualization: why might it fail? In CHI ’09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 4051–4056. https://doi.org/10.1145/1520340.1520616

- Miriam Greis, Jessica Hullman, Michael Correll, Matthew Kay, and Orit Shaer. 2017. Designing for Uncertainty in HCI: When Does Uncertainty Help? In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1145/3027063.3027091

- Henrikke Dybvik, Martin Lland, Achim Gerstenberg, Kristoffer Bjrnerud Slttsveen, and Martin Steinert. 2021. A low-cost predictive display for teleoperation: Investigating effects on human performance and workload. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 145 (2021), 102536.

- A.K. Bejczy, W.S. Kim, and S.C. Venema. 1990. The phantom robot: predictive displays for teleoperation with time delay. In Proceedings., IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. IEEE, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 546-551 vol.1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBOT.1990.126037

- A.K. Bejczy and Won S. Kim. 1990. Predictive displays and shared compliance control for time-delayed telemanipulation. In EEE International Workshop on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Towards a New Frontier of Applications. IEEE, Ibaraki, Japan, 407-412 vol.1. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.1990.262418

- James Davis, Christopher Smyth, and Kaleb McDowell. 2010. The effects of time lag on driving performance and a possible mitigation. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 26, 3 (2010), 590–593.

- Adrian Matheson, Birsen Donmez, Faizan Rehmatullah, Piotr Jasiobedzki, Ho-Kong Ng, Vivek Panwar, and Mufan Li. 2013. The effects of predictive displays on performance in driving tasks with multi-second latency: Aiding tele-operation of lunar rovers. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 57, 1 (2013), 21–25.

- Jo Vermeulen, Kris Luyten, Elise van den Hoven, and Karin Coninx. 2013. Crossing the bridge over Norman’s Gulf of Execution: revealing feedforward’s true identity. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1931–1940. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466255

- Bram van Deurzen, Herman Bruyninckx, and Kris Luyten. 2022. Choreobot: A Reference Framework and Online Visual Dashboard for Supporting the Design of Intelligible Robotic Systems. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6, EICS (2022), 151:1–151:24. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532201

- Robert R. Burridge and Kimberly A. Hambuchen. 2009. Using prediction to enhance remote robot supervision across time delay. In 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. IEEE, St. Louis, MO, USA, 5628-5634. https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.2009.5354233

- NASA Glenn Research Center. 2000. Seeing the Earth, Seeing the Moon (Earth–Moon–Earth Communication). Accessed: 2025-08-21.

- William R Ferrell and Thomas B Sheridan. 1967. Supervisory control of remote manipulation. IEEE spectrum 4, 10 (1967), 81–88.

- Günter Niemeyer, Carsten Preusche, Stefano Stramigioli, and Dongjun Lee. 2016. Telerobotics. In Springer Handbook of Robotics, Siciliano, Bruno and Khatib, Oussama (Ed.). Springer International Publishing, 1085–1108. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32552-1_43

- Yugang Liu and Goldie Nejat. 2013. Robotic Urban Search and Rescue: A Survey from the Control Perspective. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 72, 2 (2013), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10846-013-9822-x

- Marius Theissen, Leonhard Kern, Tobias Hartmann, and Elisabeth Clausen. 2023. Use-case-oriented evaluation of wireless communication technologies for advanced underground mining operations. Sensors 23, 7 (2023), 3537.

- Mark Allan, Uland Wong, P. Michael Furlong, Arno Rogg, Scott McMichael, Terry Welsh, Ian Chen, Steven Peters, Brian Gerkey, Moraan Quigley, Mark Shirley, Matthew Deans, Howard Cannon, and Terry Fong. 2019. Planetary Rover Simulation for Lunar Exploration Missions. In 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference. IEEE, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.2019.8741780

- Terry Fong. 2025. Volatiles investigating polar exploration rover. In Robotics seminar.

- Euijung Yang and Michael C. Dorneich. 2017. The Emotional, Cognitive, Physiological, and Performance Effects of Variable Time Delay in Robotic Teleoperation. International Journal of Social Robotics 9, 4 (2017), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-017-0407-x

- Justin Storms. 2016. Modeling and improving teleoperation performance of semi-autonomous wheeled robots. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Michigan.

- Santosh Mathan, Arn Hyndman, Karl Fischer, Jeremiah Blatz, and Douglas Brams. 1996. Efficacy of a predictive display, steering device, and vehicle body representation in the operation of a lunar vehicle. In Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1145/257089.257147

- Mark P Ottensmeyer, Jianjuen Hu, James M Thompson, Jie Ren, and Thomas B Sheridan. 2000. Investigations into performance of minimally invasive telesurgery with feedback time delays. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 9, 4 (2000), 369–382.

- T. Kim, P. M. Zimmerman, M. J. Wade, and C. A. Weiss. 2005. The effect of delayed visual feedback on telerobotic surgery. Surgical Endoscopy And Other Interventional Techniques 19, 5 (2005), 683–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-004-8926-6

- Ryan K Orosco, Benjamin Lurie, Tokio Matsuzaki, Emily K Funk, Vasu Divi, F Christopher Holsinger, Steven Hong, Florian Richter, Nikhil Das, and Michael Yip. 2021. Compensatory motion scaling for time-delayed robotic surgery. Surgical endoscopy 35 (2021), 2613–2618.

- Yi Zhou, Cunhua Pan, Phee Lep Yeoh, Kezhi Wang, Maged Elkashlan, Branka Vucetic, and Yonghui Li. 2021. Communication-and-Computing Latency Minimization for UAV-Enabled Virtual Reality Delivery Systems. IEEE Transactions on Communications 69, 3 (2021), 1723–1735. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2020.3040283

- Parinaz Farajiparvar, Hao Ying, and Abhilash Pandya. 2020. A Brief Survey of Telerobotic Time Delay Mitigation. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 7 (2020), 578805. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2020.578805

- Jing Du, Zhengbo Zou, Yangming Shi, and Dong Zhao. 2018. Zero latency: Real-time synchronization of BIM data in virtual reality for collaborative decision-making. Automation in Construction 85 (2018), 51-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.10.009

- Daniel Lester and Harley Thronson. 2011. Low-latency lunar surface telerobotics from Earth-Moon libration points. In AIAA Space 2011 Conference & Exposition. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), Long Beach, CA, USA, 7341.

- Miran Seo, Samraat Gupta, and Youngjib Ham. 2023. Evaluation of Performance and Mental Workload during Time Delayed Teleoperation for the Lunar Surface Construction. In Proceedings of the 2nd Future of Construction Workshop at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2023). International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction (IAARC), London, UK, 8-10. https://doi.org/10.22260/ICRA2023/0005

- Jan Leusmann, Chao Wang, Michael Gienger, Albrecht Schmidt, and Sven Mayer. 2023. Understanding the Uncertainty Loop of Human-Robot Interaction. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.07889

- Sarah Schömbs, Saumya Pareek, Jorge Goncalves, and Wafa Johal. 2024. Robot-Assisted Decision-Making: Unveiling the Role of Uncertainty Visualisation and Embodiment. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3642911

- Yudai Sato, Shuntaro Kashihara, and Tomohiko Ogishi. 2021. Implementation and Evaluation of Latency Visualization Method for Teleoperated Vehicle. In 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). IEEE, Nagoya, Japan, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1109/IV48863.2021.9575817

- G. Hirzinger, B. Brunner, J. Dietrich, and J. Heindl. 1993. Sensor-based space robotics-ROTEX and its telerobotic features. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 9, 5 (1993), 649-663. https://doi.org/10.1109/70.258056

- J. Funda, R.H. Taylor, B. Eldridge, S. Gomory, and K.G. Gruben. 1996. Constrained Cartesian motion control for teleoperated surgical robots. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 12, 3 (1996), 453-465. https://doi.org/10.1109/70.499826